‘Probably the World’s Smallest Watch Manufacturer’

As far as in-flight distractions go, Icelandair’s in-flight magazine tends to offer more than just perfume ads and the best lobster soup in Reykjavik. I was flying in from London and somewhere over the North Atlantic Sea, flipping through the glossy pages of the airline's official reading material, that I first saw an ad placement of a man who looked like he’d stepped off the set of a 1940s noir film. Paperboy hat, a loupe perched on his glasses like a monocle, hand on his chin, and a large watch next to him.

A watchmaker? In Iceland?

When you think of Iceland, puffins or Björk comes to mind. I hadn’t expected to find a watch atelier. But there it was. A short profile with just enough detail to lodge itself in the back of my mind until I touched down in Reykjavik, where I found myself walking along the city’s main shopping street, Laugavegur, in search of the improbable.

It didn’t take long to spot the black-and-white sign on the door: Probably the world’s smallest watch manufacturer. The word ‘probably’ made me laugh. It was also next to Iceland’s only Goth Store. It’s a particular brand of Icelandic humility. Bold claims softened with dry wit.

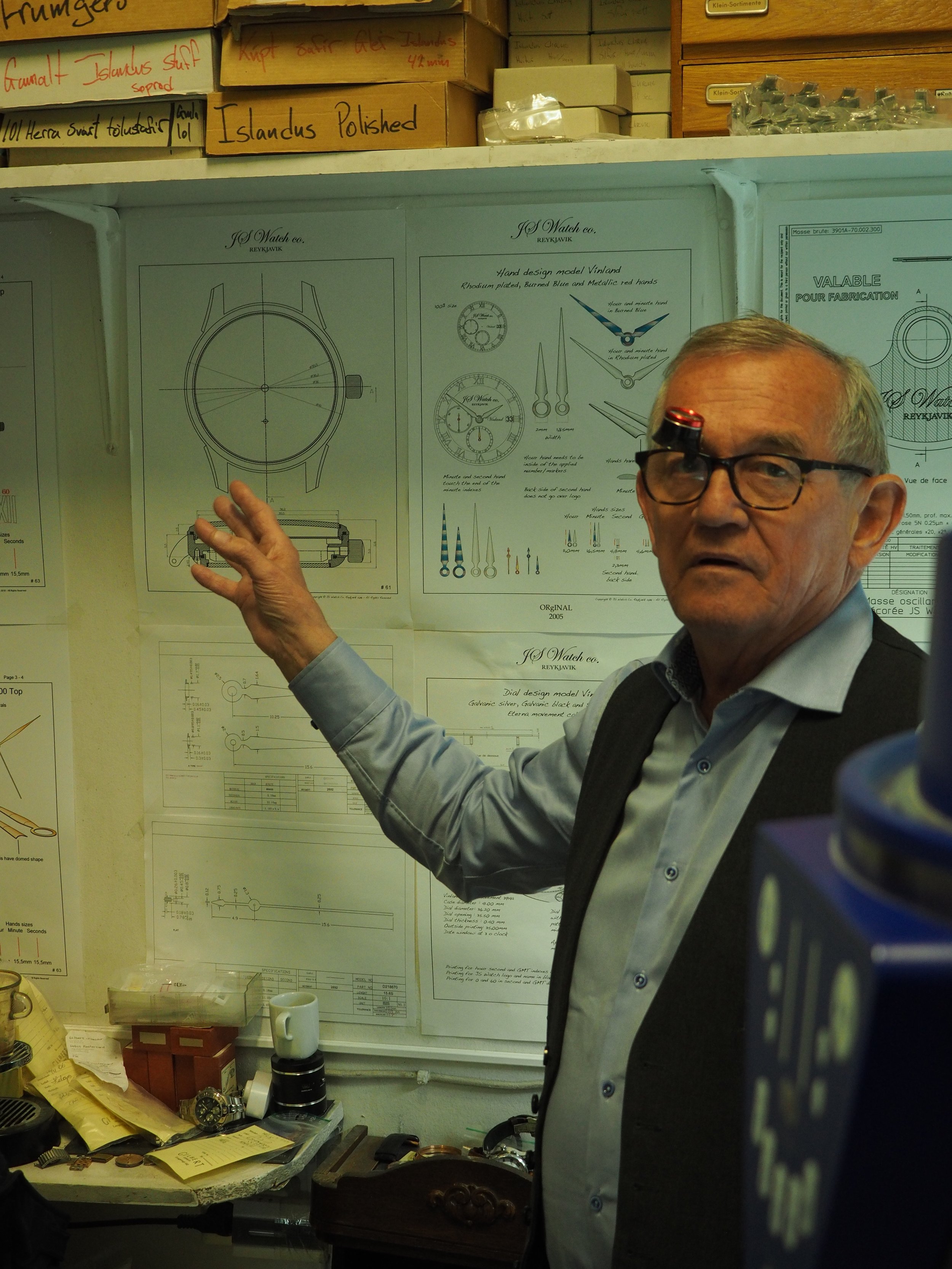

I was greeted by Gilbert and told him the ad on an Icelandair flight brought me here.

“This is it,” he said, standing up and motioning with both arms at the 270 square feet of floor space. “World’s smallest watch manufacturer. It works because I’m small.”

It’s not a gimmick. It really is small. Absurdly small for a company that’s earned an international following. Gilbert sometimes shares the space with his son, Sigurdur Gilbertsson, who is currently the technical director, and two co-founders: Grimkell Sigurthorsson, the design and marketing director, and Julius Heidarsson, a passionate collector who helped push the idea of founding their own watch brand in the early 2000s.

Though Gilbert began in the 1970s as a watch repairman, JS Watch Co. was officially born in 2005, the result of four individuals deciding to make watches exactly the way they wanted, with a healthy disregard for what the rest of the luxury watch industry was doing.

And if you’ve seen one of their ads, you’ll know what that means.

One features the team dressed as aviation mechanics, ogling a flight attendant; another has them poolside in rubber caps, dwarfed by a towering Icelandic model. In each, Gilbert appears in the foreground, absorbed in a map or a watch, comically missing the scene behind him.

“Humour is part of everything,” Gilbert told me. “There are too many serious people making serious watches.”

But behind the charm, there is rigour.

When I asked Gilbert why he became a watchmaker, why watches and not, say, cars or planes. His answer comes with a twinkle in his eye.

“I grew up traveling with my father,” he explains. “He was a radio mechanic, setting up antennas and beacons for aircraft across Iceland’s countryside. I loved being around the equipment, the tools, the small parts. So, when I was 16, I began studying radio mechanics myself.”

But it didn’t stick.

“I realized it wasn’t for me. My father had a friend, a local watchmaker, and asked if I could help him out, unpaid. That’s where I discovered my passion. Taking apart mechanical watches, figuring out how they worked, putting them back together, I was hooked. I’d work nights, weekends, skip summer holidays, just to stay at the bench. That was in 1966.”

He went on to enroll in the Technical School of Reykjavik, just before its watchmaking program was phased out. By the time quartz was decimating the mechanical industry abroad, Gilbert was quietly repairing vintage Omegas and Rolexes for a loyal local clientele. He loved the rhythm, the solitude, the intricacy. He never stopped.

By 1977, Gilbert had opened his own watch repair shop, just in time for the quartz revolution to shake the foundations of the mechanical watch industry.

“I was shocked,” he says, shaking his head. “The first digital quartz watches with red glass displays, you couldn’t repair anything. You just replaced the battery or the whole movement. I was relieved when better quartz models came along, ones you could actually service.” But the mechanical watch remained his true love.

I then asked him about why he chose Soprod over other suppliers. “We could use Sellita,” said Gilbert, seated beside a tray of half-assembled movements, “but we chose Soprod because they’re a little more independent.”

In the murky world of Swiss ébauches, movement choice is as political as it is technical. ETA, the once-ubiquitous movement maker, has been increasingly restricted under Swatch Group policy. Sellita, while independent, has come to dominate the supply chain with cloned versions of ETA’s old calibers.

Soprod, meanwhile, operates just outside the mainstream. Quiet, Swiss, and focused on quality. It’s owned by the Festina Group but maintains a degree of autonomy. The modules offer flexibility. More importantly for them, they are happy to work with smaller clients and offer direct customization.

“We want to finish the movements our own way,” Gilbert said. “We’re small enough to still care about the bridges and plates. Our customers notice those things.”

In short, Soprod gives them room to breathe.

Each year, the atelier makes no more than 900 watches. The clientele? A mix of curious travelers and diehard horological enthusiasts. Most stumble upon the shop while walking Laugavegur—perhaps, like me, lured by an ad on an Icelandair flight. Surprisingly for such a small atelier, JS Watch Co. has developed an A-list clientele more typical of Geneva than Reykjavik.

Tom Cruise discovered the brand while filming Oblivion in Iceland and became a fan. Ben Stiller followed. So did Ed Sheeran, who bought multiple pieces during a private visit and has since recommended them to friends. Even the Dalai Lama has one. Gordon Ramsay owns several JS watches, though it’s not the Michelin-starred chef who draws the most attention in Iceland.

“Gordon comes here almost every summer,” Gilbert said. “He goes salmon fishing on the north coast with my son and our business partner. Lovely guy.”

On top of being a technical director, his son also handles the modern necessities such as interfacing with customers, and managing all the digital demands of the business, while Gilbert sticks strictly to what he loves: fixing, assembling, regulating. Indeed, the generational handoff is ongoing. Sigurdur, born in the heyday of Swatch, came to mechanical watches late. But once he caught the bug, there was no turning back. And now, the family’s third generation has joined the fold: Gilbert’s grandson and Sigurdur’s son, Gilbert Sigurdsson, is now learning the craft as a young watchmaker himself.

“We’re not trying to be Patek Philippe,” he told me. “We’re trying to be ourselves. And we’re Icelandic. That means we do things differently.” That’s when I realized that JS Watch Co. isn’t just a novelty or a curiosity. It’s a reminder of what watchmaking can be at its best: small-scale, personal, rooted in place and culture, and imbued with a sense of joy.